Introduction

I hope this will be the final installment in this series, but one never knows.

Back on the summer of 2018, I wrote a short piece questioning a sensational Forbes magazine article claiming that Kylie Jenner was worth $1B, based mainly on the results of her cosmetics company. The article accepted some of the figures used by Forbes, but made adjustments for two issues that were clearly wrong, namely operating profit margins and the overall forecast period.

This past November, when it was announced that Kylie was selling 51% of her firm to Coty Inc., I revisited the valuation in light of some of the public disclosures made following the announcement, and noted that some of the figures used by Forbes were now demonstrably inaccurate:

"These numbers are far different from those presented in the Forbes piece, so different in fact that the company described by Forbes bears little resemblance to the company that Coty has actually purchased."

Well, Forbes has apparently been investigating just what went wrong with their reporting, and according this recent piece the answer is simple: they were duped, plain and simple - about historical revenues, growth rates, even about how much of the business Kylie actually owned. The corporate tax returns they shown were about as real as "reality TV".

What to Make of All This?

I enjoy reading Forbes; I find the pieces entertaining and usually informative, and their reporters are very skilled at digging up information.

But if you are placing much weight on the figures that Forbes provides for private businesses (whether it is for individuals' net worth or income or sports team valuations), the Kylie story should be a salutary reminder of the difference between a proper valuation report and a magazine article.

A proper valuation is based on a projection of the future cash flows of a business. While this projection is often informed by historic results, there are many assumptions that go into how one models the profits going forward that can have dramatic effects on the final number. These can include:

- How much will revenue grow?

- How long the growth will last before it stabilizes?

- How long will the entire business last (in some cases)?

- What will profit margins continue to be as the business grows?

- How much capital will need to be reinvested to sustain this growth?

- How will the business be capitalized (debt vs equity)?

A proper valuation report will set out these assumptions; more detailed ones will go to a fair bit of effort to support these assumptions in light of historical company data, industry level data and broad economic data.

I'm not saying Forbes doesn't do these things; maybe they do. But they certainly don't disclose their detailed assumptions, and this makes it very difficult to put much stock in their valuations.

So the next time someone tells you that a private business is worth $x, ask them some of the above questions and see what they say.

Canadian Damages Blog

Commentary on damages aspects of Canadian case law

Monday, 1 June 2020

Thursday, 2 April 2020

Expert Testimony via Web Conference - Some Personal Observations

While the courts are, for the most part, shut down right now, at least some forms of litigation are proceeding remotely. Earlier this year, I had the opportunity to be cross-examined via webcam for a large commercial arbitration. Below are some brief observations on testifying over the internet.

The Case

The circumstances in my case were somewhat different from the current situation: both sets of counsel as well as the arbitration panel were located in the same room, and I was the only person who was not physically there; the testimony was done remotely entirely for scheduling reasons. But many of these observations will likely be applicable.

The Atmosphere

I've testified many times, but courtrooms are still not a particularly relaxing place. I found being able to testify from my firm's boardroom to be a calmer experience. It was also a bit more humanizing; our boardroom is full of sports memorabilia, which drew several comments from the arbitration panel. Overall, the atmosphere was less stressful than normal.

The Connection

Experts are always told to listen to the question, think and then answer. This is easier said than done, but I found it easier to do over the internet, where there is a built-in time lag between the question being asked and the sound waves coming through the ether. It naturally slowed the pace of the cross-examination.

One drawback (at least in my case) was that there was only one webcam in the room; this was focused on counsel who was leading the cross-examination, so I was not able to see the reactions of the panel to what I was saying and whether I should elaborate on any of the points I was making.

The Documents

Our setup did not really allow counsel to put particular documents to me. He tried this a couple of times, but we did this by email so there were sometimes long pauses leading up to questions. More sophisticated platforms allow for quick sharing of documents on a computer screen, and counsel planning cross-examinations would be well advised to ensure they have this capability.

Closing

If a trial is like live theatre, then a trial over webcam is sort of like watching the Blair Witch Project in your basement. It has many of the same features, but it is just not the same.

The Case

The circumstances in my case were somewhat different from the current situation: both sets of counsel as well as the arbitration panel were located in the same room, and I was the only person who was not physically there; the testimony was done remotely entirely for scheduling reasons. But many of these observations will likely be applicable.

The Atmosphere

I've testified many times, but courtrooms are still not a particularly relaxing place. I found being able to testify from my firm's boardroom to be a calmer experience. It was also a bit more humanizing; our boardroom is full of sports memorabilia, which drew several comments from the arbitration panel. Overall, the atmosphere was less stressful than normal.

The Connection

Experts are always told to listen to the question, think and then answer. This is easier said than done, but I found it easier to do over the internet, where there is a built-in time lag between the question being asked and the sound waves coming through the ether. It naturally slowed the pace of the cross-examination.

One drawback (at least in my case) was that there was only one webcam in the room; this was focused on counsel who was leading the cross-examination, so I was not able to see the reactions of the panel to what I was saying and whether I should elaborate on any of the points I was making.

The Documents

Our setup did not really allow counsel to put particular documents to me. He tried this a couple of times, but we did this by email so there were sometimes long pauses leading up to questions. More sophisticated platforms allow for quick sharing of documents on a computer screen, and counsel planning cross-examinations would be well advised to ensure they have this capability.

Closing

If a trial is like live theatre, then a trial over webcam is sort of like watching the Blair Witch Project in your basement. It has many of the same features, but it is just not the same.

Wednesday, 1 April 2020

Business Interruption Losses for Dentists - An Introduction

You walk into your office following a long weekend, only to discover that a leaking pipe has spread several inches

of water across the floor. Moisture has penetrated the walls, and mildew is

beginning to appear on one of the chairs. You run to your office and begin

rummaging for the contact information for your insurance broker.

As a result of a small fire, Dr. Chang’s practice is closed for one month. He tells his hygienists (each of whom works one day per week at the office) that they will not be needed for the month, and does not pay them any wages. However, he continues to pay rent and office expenses, as the rent abatement clause in his lease only kicks in after 3 months.

Dealing with property insurance claims can be stressful.

And while the property damage component of the claim (that is, the costs

associated with repairing the physical damage to the office) can present its

own challenges, in my experience the greatest source of confusion and

frustration for dentists is dealing with the business interruption aspect. While

many policies provide coverage for professional fees incurred by the dentist in

order to hire a financial expert to prepare a business interruption claim, a

basic understanding of how such claims work should prove useful to all practitioners.

This

article provides a brief overview of how business interruption claims are

calculated, and then proceeds to discuss some of the thorny areas that are

particular to business interruption losses in dental practices.

What is business interruption insurance?

Business interruption policies are typically meant to place the policyholder in the financial position he or she

would have been in if not for the insured event (i.e. the flood, fire, etc.).

They do so by agreeing to pay the policyholder for any billings lost during the

‘indemnity period’, less any saved costs as a result of the incident.

Consider a simplified example. Dr. Chang runs an

established practice, having been at his current location for 30 years. He

rarely sees new patients; most patients have been with him for a long time, and

can be counted on to return every six to nine months or so. Dr. Chang averages $50,000 in

billings per month. His only major expenses are supplies, which are typically

equal to around 10% of billings, as well as $10,000 in wages paid to hygienists

and monthly rent and office expenses of $10,000. His monthly profit is

therefore $25,000, as follows:As a result of a small fire, Dr. Chang’s practice is closed for one month. He tells his hygienists (each of whom works one day per week at the office) that they will not be needed for the month, and does not pay them any wages. However, he continues to pay rent and office expenses, as the rent abatement clause in his lease only kicks in after 3 months.

The impact of the fire on Dr. Chang is that on the one

hand, he has lost $50,000 in revenue, while on the other hand he has saved on

supplies and wages. Dr. Chang’s business interruption payment for his lost revenue,

less his saved expenses, should therefore be as follows:

The business interruption payment of $35,000, combined with

the monthly rent and other office supplies of $10,000 Dr. Chang continued to pay, result in the same

monthly profit of $25,000 to which Dr. Chang was accustomed.

Other Considerations

The above example was highly simplified in order to illustrate

the basics of a business interruption loss calculation. In practice, claims are

rarely so straightforward. Common issues that can be encountered include:

- Potential ongoing losses if patients decide to move to another dentist.

- Potential to mitigate losses by rebooking patients

- Losses associated with revenue for associate dentists

- Situations where key staff continue to be paid

Different insurance policies will deal with these issues in different ways, but the basic concepts to be applied remain the same.

Wednesday, 18 March 2020

Lost Profits due to Event Cancellation - Three Things to Consider

Pretty much every public spectator event of every type –

sporting events, concerts, shows, trade shows, conferences, lectures, the Maple Leafs’ drive to the

Stanley Cup [1] - has been cancelled over the past month. In this brief article, I

will discuss some of the key issues in quantifying economic losses related to

event cancellations (regardless of the cause).

What is Being Quantified?

Some of these cancellations were at the initiative of the organizations hosting the performances; others were cancelled by the promoters; still others have been shut down due to external factors such as government restrictions.

In all cases, it is important to understand why the economic loss is being calculated, and to develop a framework for what needs to be calculated. The question to be asked, as in any damages calculation, is:

- What would have happened but for the cancellation?

- What did happen?

The framework for answering these questions may differ from case to case. For instance, if a performer cancels on an organizer and the organizer is suing for lost profits, the performer may argue that even if they had agreed to take the stage, ticket sales would have been poor anyway due to the general avoidance of public gatherings.

Revenue Losses

How much revenue will be lost by the event organizer? At a basic level, revenue can generally be lumped into two buckets: tickets, and ancillary revenues (e.g. food and beverage, parking, merchandising, broadcast rights, etc.)

The main driver for most events will generally be ticket revenue. In calculating lost ticket revenue, there are a number of factors that need to be considered:

It can be helpful (where data are available) to review historic sales patterns to assist in modeling lost ticket sales that would have been made but for the cancellation.

Obviously, venue capacity is a limiting factor in any such analysis.

But others major costs may not be saved. One of the major costs for most events is the fees paid to the performers. These can come in many forms, but in general they contain a fixed component that is non-refundable. Venue fees may also be (at least partially) non-refundable. For these types of costs, it is critical to understand what the contractual arrangement was between the parties and to determine what amounts have actually been paid and what amounts each party remains liable for.

Conclusion

Organizing a major event is a complex enterprise, and proper calculation of economic loss from the cancellation of the event involves getting a full understanding of all of the different moving parts: the performers, the venue, the contracts and revenue streams.

[1] This is an annual event in Toronto that typically begins in mid-April and ends a week or two later.

[2] Table taken from J. Suher, “Forecasting Event Ticket Sales”, University of Pennsylvania Scholarly Commons, 5-1-2008

What is Being Quantified?

Some of these cancellations were at the initiative of the organizations hosting the performances; others were cancelled by the promoters; still others have been shut down due to external factors such as government restrictions.

In all cases, it is important to understand why the economic loss is being calculated, and to develop a framework for what needs to be calculated. The question to be asked, as in any damages calculation, is:

- What would have happened but for the cancellation?

- What did happen?

The framework for answering these questions may differ from case to case. For instance, if a performer cancels on an organizer and the organizer is suing for lost profits, the performer may argue that even if they had agreed to take the stage, ticket sales would have been poor anyway due to the general avoidance of public gatherings.

Revenue Losses

How much revenue will be lost by the event organizer? At a basic level, revenue can generally be lumped into two buckets: tickets, and ancillary revenues (e.g. food and beverage, parking, merchandising, broadcast rights, etc.)

The main driver for most events will generally be ticket revenue. In calculating lost ticket revenue, there are a number of factors that need to be considered:

1)

Refunds on tickets sold prior to the

cancellation

This number is generally relatively straightforward, as it

will be well documented. Issues can arise over what the organizer’s actual

cancellation and refund policy is, and if customers are entitled to refunds or

simply credits towards future events. If the latter, then the cancellation may

not reflect an actual revenue loss, merely a deferral.

2)

Projected future tickets sold

The more challenging exercise is determining how many more

tickets would have been sold between the time of the cancellation and the date

of the event.

It is important to understand that for many events, ticket

sales do not follow a linear pattern. There is a large block that tends to get

sold as soon as tickets are released, another surge in the first few weeks, and

then another large surge in the days before the event, particularly for lower

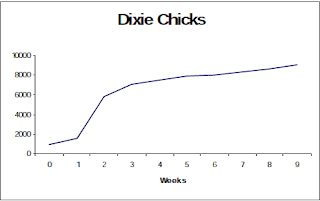

priced tickets. Here is an example from one concert:[1]

It can be helpful (where data are available) to review historic sales patterns to assist in modeling lost ticket sales that would have been made but for the cancellation.

Obviously, venue capacity is a limiting factor in any such analysis.

Saved Expenses

As a result of the event failing to occur, some expenses

will be saved (e.g. the cost of food and beverages that would have been sold,

or the cost of event staff); these will need to be offset against the revenue loss. But others major costs may not be saved. One of the major costs for most events is the fees paid to the performers. These can come in many forms, but in general they contain a fixed component that is non-refundable. Venue fees may also be (at least partially) non-refundable. For these types of costs, it is critical to understand what the contractual arrangement was between the parties and to determine what amounts have actually been paid and what amounts each party remains liable for.

Conclusion

Organizing a major event is a complex enterprise, and proper calculation of economic loss from the cancellation of the event involves getting a full understanding of all of the different moving parts: the performers, the venue, the contracts and revenue streams.

[1] This is an annual event in Toronto that typically begins in mid-April and ends a week or two later.

[2] Table taken from J. Suher, “Forecasting Event Ticket Sales”, University of Pennsylvania Scholarly Commons, 5-1-2008

Thursday, 28 November 2019

Is Kylie Jenner a Billionaire, or Even Close? Part II

A little over a year ago, I wrote a short blog post taking issue with a Forbes magazine article that had concluded that Kylie Jenner’s company, Kylie Cosmetics was worth over $1B. In light of last week’s news that Coty Inc., a publicly traded cosmetics firm, is purchasing a 51% share in Kylie Cosmetics for $600M, this would seem to confirm that Forbes was right and I was wrong. Or does it?

I’ll begin by making a few technical observations. The Forbes article had stated that Kylie’s revenue for 2017 was $400M, and pre-tax profit margins (it seemed to imply) were in the range of 40%, for pre-tax profit of around $160M.

The public disclosures so far surrounding the Coty transaction appear to indicate that in fact:

Now, Ms. Jenner stands to receive $600M in cash for the 51% of her company. $600M is worth $600M; not even I can argue otherwise. But what is her remaining 49% interest in her company worth? Ostensibly, if 51% of her company is worth $600M (which is what Coty is paying for it), then the other 49% should be worth a little bit less than $600M, which would put Ms. Jenner at around $1.2B. Or does it?

There are a few points worth considering:

I’ll begin by making a few technical observations. The Forbes article had stated that Kylie’s revenue for 2017 was $400M, and pre-tax profit margins (it seemed to imply) were in the range of 40%, for pre-tax profit of around $160M.

The public disclosures so far surrounding the Coty transaction appear to indicate that in fact:

- Revenue for the last twelve months has been only $177M, which represents growth of 40% over calendar 2018. This would seem to imply that revenue in calendar 2018 was around $125M.

- EBITDA margins are “>25%”

Now, Ms. Jenner stands to receive $600M in cash for the 51% of her company. $600M is worth $600M; not even I can argue otherwise. But what is her remaining 49% interest in her company worth? Ostensibly, if 51% of her company is worth $600M (which is what Coty is paying for it), then the other 49% should be worth a little bit less than $600M, which would put Ms. Jenner at around $1.2B. Or does it?

There are a few points worth considering:

- Coty is a beauty-care company with a market cap that has hovered in the range of $9B, with annual revenues of around $9B. Its business has been performing poorly and it was looking for a way to reconnect with a younger demographic. Ms. Jenner fits that bill. So a large portion of the $600M Coty paid for Ms. Jenner’s shares is likely represented in the synergistic or knock-on effects it feels that Ms. Jenner’s small company will have on Coty’s results. These are benefits that, as a shareholder of a 49% stake in Kylie Cosmetics, Ms. Jenner does not necessarily get to participate in.

- Second, the stock market’s reaction to the deal has not been particularly enthusiastic. Coty’s market capitalization has fallen by around $300M (from $9.0B to $8.7M) in the week or so since the deal was announced. So while Coty may have paid $600M for Kylie Cosmetics, it is less than clear that Coty’s investors feel that this was fair market value for the company.

- Finally, Ms. Jenner is now a minority shareholder in her company, and her ownership interest may be valued at less than her pro-rata interest in her company. The details of the deal have not been disclosed, so it is unclear how much representation Ms. Jenner will retain on the board of her own firm. But this is something that could potentially have an impact on the value of the remaining 49% of the business.

Wednesday, 11 September 2019

Thursday, 25 July 2019

Calculating Damages in Representations and Warranties Cases

Introduction

Mergers and acquisitions (“M&A”) can be a double-edged sword. When done right, M&A can allow acquirers to scale their businesses and create value through synergies. When done poorly, M&A can result in drastic overpayments for assets that are not nearly as valuable as believed and for economies of scale that are very difficult to achieve.

One of the main risks in M&A is information asymmetry: simply put, the vendor knows much more about its business than the acquirer. While the acquirer is able to perform due diligence, time pressures to close the deal mean that this process can sometimes be imperfect; issues are sometimes missed. This is where Representations and Warranties (R&W) insurance can come into play. This brief article provides a brief overview of R&W insurance, and discusses some of the issues we have encountered as forensic accountants and business valuators in quantifying losses under this type of insurance coverage.

Long-term misrepresentations will tend to involve the income statement. For instance, in one case we were recently involved in, the seller had represented to the purchaser that it was not subject to a particular type of property tax. This turned out to be incorrect, and as a result the purchaser was liable to pay this additional, unexpected amount every year for the foreseeable future. In that case, the loss to the purchaser is equal to the present value of the ongoing annual tax liabilities.

How does one value these sorts of long-term misrepresentations? One shorthand approach might be to simply apply the acquisition multiplier to the value of the annual misstatement. For instance, if the deal multiplier was 10 times the seller’s trailing EBITDA, and the value of a misrepresentation (such as the unreported property tax issue) is $1M per year, then one might reasonably conclude that the value of the misstatement is $10M.

This approach can be appropriate in some cases, but sometimes it can lead to incorrect results, when the cash flows associated with the misrepresentation in question have different characteristics (term, riskiness or growth forecast) than the acquired business as a whole. Consider the following example:

This article first appeared in the July 25, 2019 edition of Lawyer's Daily, published by LexisNexis Canada

Mergers and acquisitions (“M&A”) can be a double-edged sword. When done right, M&A can allow acquirers to scale their businesses and create value through synergies. When done poorly, M&A can result in drastic overpayments for assets that are not nearly as valuable as believed and for economies of scale that are very difficult to achieve.

One of the main risks in M&A is information asymmetry: simply put, the vendor knows much more about its business than the acquirer. While the acquirer is able to perform due diligence, time pressures to close the deal mean that this process can sometimes be imperfect; issues are sometimes missed. This is where Representations and Warranties (R&W) insurance can come into play. This brief article provides a brief overview of R&W insurance, and discusses some of the issues we have encountered as forensic accountants and business valuators in quantifying losses under this type of insurance coverage.

What is R&W

Insurance?

R&W insurance provides indemnity for “losses” related to

overpayment by the acquirer resulting from breaches of representations and warranties

as set out in the purchase agreement for the acquisition.

These types of policies are becoming increasingly popular.

One global

broker recently reported a 30% increase in deals written in 2018

compared with the prior year. The average policy limit was equal to 15% of the

total enterprise value of the deal (e.g. a deal for $100M would have a policy

limit of $15M); while deductibles were generally set at 1% of enterprise value.

The same publication also reported that premiums have been declining over the

past two years, as more insurers enter this market. Another publication

by a leading insurer in the space mentions that the frequency of claims has

been roughly one claim for every five transactions.

Two types of mistakes

Based on our experience quantifying

losses under R&W coverage, there are two main types of misrepresentations:

one-time misrepresentations and long-term misrepresentations.

One-time misrepresentations

These types of misrepresentations

generally relate to the balance sheet. M&A transactions typically will set

a target level of “net working capital”, based on an overall understanding of

the subject company. If issues with this calculation are discovered following

the closing, the economic loss to the purchaser is generally equal to the

amount of the misstatement.

Quantifying these types of issues

involves first obtaining a detailed understanding of the components of the

purchase price and ensuring that the alleged misrepresentations are not already

factored into the price. For example, if the claim is that a large amount of

inventory had to be written off following closing, one would need to make sure

that the inventory balance included in the closing statements did not already

consider a provision for obsolete inventory.

Long-term

misrepresentations Long-term misrepresentations will tend to involve the income statement. For instance, in one case we were recently involved in, the seller had represented to the purchaser that it was not subject to a particular type of property tax. This turned out to be incorrect, and as a result the purchaser was liable to pay this additional, unexpected amount every year for the foreseeable future. In that case, the loss to the purchaser is equal to the present value of the ongoing annual tax liabilities.

How does one value these sorts of long-term misrepresentations? One shorthand approach might be to simply apply the acquisition multiplier to the value of the annual misstatement. For instance, if the deal multiplier was 10 times the seller’s trailing EBITDA, and the value of a misrepresentation (such as the unreported property tax issue) is $1M per year, then one might reasonably conclude that the value of the misstatement is $10M.

This approach can be appropriate in some cases, but sometimes it can lead to incorrect results, when the cash flows associated with the misrepresentation in question have different characteristics (term, riskiness or growth forecast) than the acquired business as a whole. Consider the following example:

·

The business being sold has two divisions, Rapid

Robotics and Flat Pancakes. After-tax cash flows last year were $10M ($5M for

each division), and the business recently sold for $200M, or 20 times after-tax

cash flows.

·

It was discovered that due to regulatory changes

in the pancake market (which were known to the seller prior to the deal), Flat

Pancakes will need to eliminate a particular product line that accounted for

$1M in after-tax cash flows. The purchaser advances a claim for $20M, equal to

the annual value of the misrepresentation of $1M times the acquisition

multiplier of 20 times.

·

The problem with this approach is the 20x multiplier

may actually consist of a multiple of 30 times cash flows for the Rapid

Robotics division, and only 10 times cash flows for the Flat Pancakes division.

The higher multiplier for Rapid Robotics would represent the value attributed

by the purchaser to the anticipated growth in that division.

·

This means that the value of the $1M

misrepresentation in the slow-growth Flat Pancakes division is only $10M, not

$20M.

In order to perform a proper analysis of these longer-term

misrepresentations, it is therefore generally very beneficial to obtain a copy

of the valuation model used by the acquirer in the transaction in order to understand

how the transaction multiplier was arrived at and to reverse engineer the

impact of the particular misrepresentation on business value.

Closing

This article has only scratched the surface of the types of

issues that, in our experience, can arise from post-acquisition M&A

disputes. As M&A insurance becomes, in the words of one

insurer, “the new normal”, we will no doubt have the opportunity to

revisit this topic in future articles.This article first appeared in the July 25, 2019 edition of Lawyer's Daily, published by LexisNexis Canada

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)