What is Being Quantified?

Some of these cancellations were at the initiative of the organizations hosting the performances; others were cancelled by the promoters; still others have been shut down due to external factors such as government restrictions.

In all cases, it is important to understand why the economic loss is being calculated, and to develop a framework for what needs to be calculated. The question to be asked, as in any damages calculation, is:

- What would have happened but for the cancellation?

- What did happen?

The framework for answering these questions may differ from case to case. For instance, if a performer cancels on an organizer and the organizer is suing for lost profits, the performer may argue that even if they had agreed to take the stage, ticket sales would have been poor anyway due to the general avoidance of public gatherings.

Revenue Losses

How much revenue will be lost by the event organizer? At a basic level, revenue can generally be lumped into two buckets: tickets, and ancillary revenues (e.g. food and beverage, parking, merchandising, broadcast rights, etc.)

The main driver for most events will generally be ticket revenue. In calculating lost ticket revenue, there are a number of factors that need to be considered:

1)

Refunds on tickets sold prior to the

cancellation

This number is generally relatively straightforward, as it

will be well documented. Issues can arise over what the organizer’s actual

cancellation and refund policy is, and if customers are entitled to refunds or

simply credits towards future events. If the latter, then the cancellation may

not reflect an actual revenue loss, merely a deferral.

2)

Projected future tickets sold

The more challenging exercise is determining how many more

tickets would have been sold between the time of the cancellation and the date

of the event.

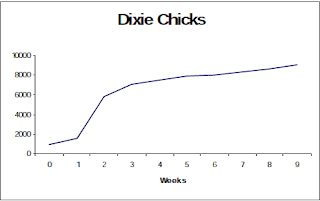

It is important to understand that for many events, ticket

sales do not follow a linear pattern. There is a large block that tends to get

sold as soon as tickets are released, another surge in the first few weeks, and

then another large surge in the days before the event, particularly for lower

priced tickets. Here is an example from one concert:[1]

It can be helpful (where data are available) to review historic sales patterns to assist in modeling lost ticket sales that would have been made but for the cancellation.

Obviously, venue capacity is a limiting factor in any such analysis.

Saved Expenses

As a result of the event failing to occur, some expenses

will be saved (e.g. the cost of food and beverages that would have been sold,

or the cost of event staff); these will need to be offset against the revenue loss. But others major costs may not be saved. One of the major costs for most events is the fees paid to the performers. These can come in many forms, but in general they contain a fixed component that is non-refundable. Venue fees may also be (at least partially) non-refundable. For these types of costs, it is critical to understand what the contractual arrangement was between the parties and to determine what amounts have actually been paid and what amounts each party remains liable for.

Conclusion

Organizing a major event is a complex enterprise, and proper calculation of economic loss from the cancellation of the event involves getting a full understanding of all of the different moving parts: the performers, the venue, the contracts and revenue streams.

[1] This is an annual event in Toronto that typically begins in mid-April and ends a week or two later.

[2] Table taken from J. Suher, “Forecasting Event Ticket Sales”, University of Pennsylvania Scholarly Commons, 5-1-2008

No comments:

Post a Comment